Actual dames

Lords honours Nelson Mandela’s life at Parliament’s commemoration and celebration event/Copyright House of Lords 2013/Photography by Roger Harris/Flickr

Our Betty

There are Dames, wannabe Dames…and then there are those who exceed Damery and move straight to Baroness. Betty Boothroyd is a case in point.

The indomitable former Speaker of the House of Commons, and the only woman to occupy this role to date, appears never to have quite done things by the book. In a fascinating interview with Jo Coburn for the BBC , she wonders whether “perhaps I came out of the womb into the Labour movement”. And perhaps she did.

She was born into a working-class family in Dewsbury in 1929, one that had little money but made up for it in love and warmth. In Betty Boothroyd, The Autobiography, she explains what she has always stood for: fair play, an unshakeable sense of honour and a passionate belief in the sovereignty of Parliament.

Baroness Boothroyd trod a very circuitous route to that particular House, though. A love of dance from an early age led to her becoming a talented dancer, and at the age of 17 she pursued a brief career with the celebrated Tiller Girls. But it wasn’t to last, and eight years later her dreams of taking the West End by storm were over.

It doesn’t seem the most logical next step, but despite her father’s hopes of seeing her settled into a nice safe job, she won a national speaking award, put herself up for election to the local council and became a full-time worker for the Labour Party. She has been involved with politics ever since. It wasn’t always an easy ride, though. Despite working at the House for Barbara Castle and Geoffrey de Freitas she went on to lose two by-elections, leaving the UK to campaign for JFK in the US.

On her return, and with a plum job working for Labour Minister Lord Harry Walston, she was admitted to the inner circle of the socialist elite and finally gained the parliamentary seat she craved in 1973. Nineteen years on she was appointed to the role she made famous, Speaker of the House.

She has always been a role model of mine. I watched, fascinated, at the way she kept order in the House seemingly effortlessly. She was firm but charming with it, and her black robes never seemed to overwhelm her glamour but instead enhanced it. And now she is in the House of Lords, she continues to speak her mind. Earlier this year she lambasted ‘insulting’ MPs after they completed their work in just three hours one Monday, five hours earlier than scheduled, claiming the hours were “an insult to the Parliamentary system”, which was being “diminished in the eyes of the electorate”.

Right on, Betty. You tell ‘em. Her fervour and her energy appear undimmed by age or health problems. After a heart valve replacement surgery in 2009 – on the NHS, of course – she suffered acute renal failure and didn’t come round until four days after surgery. To this day she remembers nothing about being in intensive care.

The operation took its toll, but by the end of that year she was given a clean bill of health, left for a holiday in Cyprus, and was even able to wear a two-piece swimming costume. The episode also made her give up smoking and now, firmly ensconced in the House of Lords, she appears trimmer and fitter than ever.

I admire her for taking up paragliding in her 60s (who knows, I may yet follow in her footsteps), an activity she describes as “lovely and peaceful” and “exhilarating”. The list of organisations with which she’s still involved in her public life, meanwhile, ranging from Education Respite Care for Children (SMILE) to The Middle Temple, is seemingly endless, encompassing her time as Chancellor of the Open University.

If only I knew what vitamin pills she was on, I’d order a truck load. But the sad fact is, it’s probably genetic. Baroness Boothroyd, we salute you. Long may you flourish.

Dame Rebecca West, 1892–1983

Rebecca West was my kind of dame. She seems to have had everything – brains, courage, a free and independent spirit, a strong feminist commitment, a love of travel, journalistic enquiry and a formidable writing talent. She was born in Ireland in 1892 as Cecily Isabel Fairfield and her formal education ended at 16. The family moved to London and she studied acting. At this time she became inspired by the rebel heroine Rebecca West in Ibsen’s play Romersholm and changed her name accordingly.

Rebecca and her older sister Lettie became active supporters of the women’s suffrage movement and participated in street marches in support of the cause. Her writing career started at this time with journalistic contributions to The Freewoman, a weekly feminist journal advocating free love and the right for women to remain unmarried. She also wrote for The New Freewoman, a literary magazine and for The Clarion, a socialist newspaper. At the age of 20, in 1912, she wrote an outspoken review for The Freewoman of H.G. Wells’ book Marriage. This led to their meeting and then to a 10-year affair with Wells and the birth of her only son, Anthony West. Wells was already married, but had a number of extra marital relationships. West later married a banker, Henry Maxwell Davies, and their marriage lasted until his death.

Rebecca wrote seven novels but her political awareness was as important to her mind set as her fictional skills. Her life spanned the two great wars of the 20th century, the Russian revolution and the Spanish Civil War. She wrote extensively on feminist and socialist causes, frequently visiting the USA to give lectures and be involved in socialist issues there. Although firmly left of centre and a staunch anti-fascist – she sent money to the Republican cause in Spain during the Civil War – she was also anti-communist, which did not endear her to many on the left who supported communist ideals. She considered Stalin a criminal whose extreme authoritarianism denied true communists independence and freedom, values she passionately upheld. The brutal expansion of the Soviet Union following the Second World War confirmed her views as she witnessed many countries in Eastern Europe forced behind the Iron Curtain.

It was Eastern Europe that provided the material for West’s finest book, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, A Journey through Yugoslavia. Published in two volumes in 1941 at the height of the Second World War, it gives a detailed history and analysis of the region which West gained during three extended trips to the country from 1936-1938. Part travel book, part history, part reportage, the depth of the material and the insights we gain as we travel through the countries that constituted Yugoslavia are astounding. In 1943 she was furious at the Allies’ decision to back Tito’s communists, which subsequently resulted in Tito’s Presidency of Yugoslavia until his death in 1980.

West was commissioned by the New Yorker magazine to report on the Nuremberg trials at the end of World War II; her book A Train of Powder records this experience. In the 1960s she reported on apartheid in South Africa for The Sunday Times.

She continued to travel extensively in later life and wrote prolifically until the end; much of her later work was published posthumously. She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1959, in recognition of her extraordinary contribution to British letters.

In the past, many of the women who have been awarded DBEs or Dame Commanders of the British Empire (yes, no one seems to have told the people in authority that recent history would suggest that the Empire no longer exists, despite the apparent desire of some Brexiteers to reconstitute it) came from well-to-do families, which afforded them the financial security to go on and do the good works which earned them the damehood. I am not for a moment belittling these women’s achievements – when I learn of their lives and work I am genuinely humbled by how much they have done.

Nevertheless, the life and successes of Dame Beatrice Anne Godwin are particularly notable when one learns that she left school at 15 to become a counting house clerk for a London store, working 10 hours a day on a 6-day week, for 5 shillings a week, or 20p. That equates roughly to £71 in today’s money, although during sales times she worked an extra 3 hours a day, which earned her a free supper.

During the First World War Godwin worked as an Army pay clerk. Requests by the women workers for higher wages were flatly refused, which marked the beginning of Godwin’s interest in unions and collective bargaining. In 1920 she joined the newly created Association of Women Clerks and Secretaries (AWCS), becoming a full time official – the London organiser – in 1928. The union had to battle hard to obtain rates of pay that were comparable with those of their male counterparts.

Much of Anne and her compatriots’ energies were spent in raising the awareness of the AWCS, whose members were female civil servants employed on a temporary basis. After 1930, many of the women were made permanent employees, which meant they were obliged to join the National Association of Women Civil Servants. The vacancies in the administration of the AWCS created by these movements gave Godwin opportunities to move up the ranks, chances which she seized on.

The 1930s saw the beginning of negotiations on the possible amalgamation of the AWCS with the National Union of Clerks. Godwin was in charge of negotiation and general administration, and when the merger was formalised at the end of 1939, she was appointed Assistant General Secretary of the newly created Clerical and Administrative Workers Union (CAWU), with guaranteed attendance at the Trades Union Congress (TUC) Conference for five years. Godwin also edited the union’s journal The Clerk.

In 1949, one of the seats on the TUC General Council reserved for women became vacant, and Godwin won the ballot, serving until her retirement in 1962. She also became General Secretary of the CAWU in 1956; her management style was widely appreciated. She was a firm believer in equality of opportunity and that women and men should receive equal pay for the same work. One wonders what she would have made of some of the recent revelations regarding pay grades at the BBC.

Godwin was also a great believer in education, serving on the National Trade Union Committee of the Workers’ Educational Association. She also campaigned for more higher education opportunities for working men and women.

Dame Anne Godwin spent the last year of her career as President of the TUC – one of the first women in this role – and was awarded the DBE in 1962. She left a strong record of committed involvement to improving the lives and working conditions of all working men and women.

Scroll down for profiles of Dame Cicely Veronica Wedgwood, Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Dame Julia Slingo, and Dame Margaret Hodge.

![]()

Dame Cicely Veronica Wedgwood, 1910-1997

One of the joys of damesnet as far as I’m concerned is discovering the breadth of talent and skills amongst the many and varied dames who have contributed to and enriched our lives over the years. July 20th is the birthday of the historian Dame Cicely Veronica Wedgwood.

A great-great-great granddaughter of the potter Josiah Wedgwood, she was born in Northumberland and got a First in Classics and Modern History at Oxford. She went on to specialise in European history of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her work in continental European history included the major study The Thirty Years War (1938), when she was still in her 20s, and biographies of William the Silent and Cardinal Richelieu. She devoted the greater part of her research to English history, especially in the English Civil War. Her major works included a biography of Oliver Cromwell and two volumes of a planned trilogy, The Great Rebellion, which included The King’s Peace (1955) and The King’s War (1958). She continued the story with The Trial of Charles I (1964).

Her work drew praise and acclaim from other historians, writers and critics, including A.L. Rowse, Patrick Leigh Fermor and George Steiner. It was said that in her writing she managed to successfully tread the middle ground between popular and scholarly works. This involved a narrative approach which focused on the ‘how’ rather than the ‘why’, and she was considered the most distinguished woman historian of her time. In her view, historians should do more than analyse and describe, which led to the Economist writing that she “had a novelist’s talent for entering into the character of the giants of history.”

She enjoyed, in addition, an American career. For 15 years, from 1953 to 1968, she was a member of the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton, which had been founded on the model of All Souls College, Oxford. This gave her an opportunity to concentrate on research and writing. She was rewarded with numerous American honours, membership of the Academies of Arts and Letters, and Arts and Sciences, and the Philosophical and Historical Societies.

Her success extended to lecturing and broadcasting; in 1953 the BBC invited her to present her impressions of the coronation on Queen Elizabeth II. She received a number of honorary degrees from the universities of Glasgow, Sheffield, and Smith College in the US, and was awarded the Goethe Medal in 1958.

As well as her academic and writing achievements, she was President variously of the International Pen Club, the Society of Authors and the London Library. She served on the Arts Council and the Advisory Council of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and was a trustee of the National Gallery – its first female trustee.

She was created a CBE in 1956 and a DBE in 1968. Then in 1969 she became the third woman to be appointed a member of the British Order of Merit. Her life partner for nearly 70 years was Jacqueline Hope-Wallace CBE, and they lived together in Polegate in Surrey.

With this dizzying list of achievements, it is hard to accept that a woman of this calibre felt the need to write under the nom de plume of C.V. Wedgwood to avoid any possible discrimination against a woman historian. What an extraordinary dame.

![]()

Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett

Here at damesnet we love our dames, and continue to invite all our readers to nominate women for damehood. But there are of course many actual dames worthy of our attention, and 11 June sees the birthday of one of the UK’s most important dames in the history of female emancipation.

Here at damesnet we love our dames, and continue to invite all our readers to nominate women for damehood. But there are of course many actual dames worthy of our attention, and 11 June sees the birthday of one of the UK’s most important dames in the history of female emancipation.

Born in 1847, Millicent Garrett was the younger sister of Elizabeth Garrett, the first British woman to qualify as a physician and a surgeon. Both sisters were suffragists, and for 50 years Millicent led the movement for women’s suffrage in England. Her marriage to Henry Fawcett was mutually beneficial: he was a radical politician and professor of political economy at Cambridge University, who had been blinded as a young man in a shooting accident. Millicent helped him overcome this handicap, and Henry supported her campaign for women’s rights.

Inspired by the work of John Stuart Mill, who was a passionate advocate for equal rights for women, in 1866 she became the Secretary of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. In 1868 she joined the London Suffrage Committee, where she made her first speech on the subject. She wrote and published essays and text books; the first of these was Political Economy for Beginners, published in 1870.

She did not agree with the confrontational and at times violent activities of the Pankhurst family and their supporters in the Women’s Social and Political Union; Millicent felt that their militancy was working against public opinion, and promoted a more moderate approach. In 1890 she became the leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), a post she held until 1919, a year after some 6 million women over the age of 30 in the UK were granted the vote, providing that they or their husbands met a property qualification. During the First World War she kept up the NUWSS campaign, and the organisation contributed to the cause by drawing attention to how women were helping and supporting the war effort.

Alongside her campaign for voting rights, Fawcett worked hard to improve the provision of higher education for women, co-founding Newnham College at Cambridge in 1875. She also supported numerous other campaigns to improve conditions for young women and girls. They included efforts to combat child abuse by raising the age of consent. In 1885 the age of consent was raised to 16, only 10 years after it had been raised to 13 in 1875. Millicent also campaigned for incest and cruelty to children in the family to be criminalised. She fought to have the Contagious Diseases Acts repealed; they required prostitutes to be examined for sexually transmitted diseases, and to be imprisoned if they were found to be infected, or even if they refused to undergo painful examinations. Their male clients, however, were not required to be examined. Apart from her ongoing battle for women’s suffrage, this was one of the more successful campaigns she fought.

She was awarded a damehood in 1925, four years before her death. Earlier this year, it was announced that a statue of Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett has been commissioned for the centenary celebrations of The Representation of the People Act, passed in 1918. The statue will be erected in Parliament Square – the first woman to be honoured with a statue in this iconic location. Let’s hope she will also be the first of many more monuments across the country to women who have contributed to national life. (See inVISIBLEwomen.org.uk for how to campaign for more.

![]()

Dame Julia Slingo

To coincide with the UN 2015 Conference on Climate Change taking place in Paris at the time of writing, I have been finding out more about Dame Julia Slingo, Chief Scientist at the Met Office since 2009. Her job involves managing over 500 other scientists, in charge of research that ranges from creating tomorrow’s weather forecast to developing models of what the climate will be like in the next century.

Looking at her CV and experience, it is hard to know how to prioritise her extraordinary achievements. I wonder just how many women – or men – can list their areas of expertise as:

- climate modelling

- tropical weather and climate

- monsoons of India and China, as well as El Niño

- climate change and its impacts

Julia Slingo graduated with a degree in physics at Bristol University in 1973 and was then offered a job at the Met Office. In 1986 she moved to the National Centre for Atmospheric Research in the US; during this time she was awarded a PhD in atmospheric physics from Bristol University.

Prior to taking up her current role at the Met Office, she was the Director of Climate Research at the NERC National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading, and remains Professor of Meteorology there, which meant that she was the first female in the UK to hold such a post. In 2006 she founded the Walker Institute for Climate System Research at Reading.

Reading interviews that she has conducted in recent years, I am struck by her total commitment to the scientific method:

“I’ve always been curiosity-driven and it’s always given me enormous pleasure. So that’s why I came into meteorology, because I could see physics working outside.” She has confirmed time and again that “I always stick to what the science says.” This commitment has served her well in recent years when the Met Office has become a target for condemnation. Once such instance concerned the prediction of a “barbecue summer” in 2009, the year Slingo took up her post. The actual summer was far from barbecue friendly and the Met Office took a lot of stick.

Slingo pointed out that what the Met Office had actually said was that it was “odds on for a barbecue summer”, so probabilistic and therefore neither right nor wrong. She has acknowledged that, nevertheless, the incident did serve as a wake-up call – the Met Office has studied the issues around seasonal forecasting and how probabilities are communicated to the general public, and improved its performance in this area.

The criticism became personal when former Chancellor Nigel Lawson, who is not a scientist, and a sceptic on the topic of climate change, denied any connection in 2014 between flooding in the UK and climate change. He referred to Slingo as “this Julia Slingo woman who made this absurd statement”. Fortunately Dame Slingo had the knowledge and sense to rise above such sexist, contemptible language.

The achievements, awards and accolades have continued to flood in (if you’ll pardon the pun): in 2008 she became the first woman President of the Royal Meteorological Society. In the same year she was awarded an OBE for services to environmental and climate science. In 2014 Slingo was named as one of the 100 leading UK practising scientists by the Science Council and became a Dame for services to weather and climate science. This year, 2015, saw her elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Nigel Lawson – cap that if you can.

Dame Margaret Hodge

In 2015, one of the new nominees for damehood that the dames were very pleased to observe was Margaret Hodge, Labour MP for Barking since 1994. Dame Margaret combines a keen intellect and a probing mind with a refusal to be fobbed off. Nowhere was this more evident than when she was the head of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) from 2010 – 2015.

In 2015, one of the new nominees for damehood that the dames were very pleased to observe was Margaret Hodge, Labour MP for Barking since 1994. Dame Margaret combines a keen intellect and a probing mind with a refusal to be fobbed off. Nowhere was this more evident than when she was the head of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) from 2010 – 2015.

There seemed to be a time when barely a week would go by without the edifying spectacle of Ms Hodge subjecting a captain of industry/government chief/political aide to a verbal interrogation that invariably had the victim shifting and squirming. I took huge vicarious pleasure in watching these exchanges. Whenever her busy schedule allowed it, my grandmother used to spend some of Saturday afternoons watching live sport on the TV. Her particular favourite, to the amazement of her bemused family, was the wrestling. She would shout and cheer from her armchair as the two opponents battled their way through the match.

While I never shared my grandmother’s particular passion, I now understand where she was coming from. I have found myself on several occasions cheering on the redoubtable PAC Chair with as much noise and excitement as my forbear.

Our dame was born Margaret Eve Oppenheimer in Cairo, one of five children to émigré parents from Germany and Austria. The family moved to England in 1948, following the Arab-Israeli War the same year.

After studying at the LSE, Hodge worked at Unilever, Weber Shandwick and Price Waterhouse before election to Islington Council in 1973, subsequently becoming Chair of the Housing Committee, where she presided over a major housing programme. She was Council Leader for Islington from 1982 – 1992, at which point she left politics, only to return as MP for Barking two years later.

She became a Junior Minister in 1998, and was appointed Minister for Universities in 2001. A new post of Minister for Children was created for her in 2003, but controversy surrounding her from an incident during her time at Islington Council resulted in her being transferred to other posts. This related to claims by an individual of abuse at a children’s home in Islington while Hodge was Leader of the Council.

Like any independent woman, Margaret Hodge has a reputation for being outspoken, which has caused problems in her political career on a number of occasions. In 2006 in a newspaper interview she said that white working class voters might be tempted to vote BNP because “no one else is listening to them”. This caused a furore in the media and within the Labour Party. However, she was vindicated in the 2010 election, when she doubled her majority and the BNP came in at third place. The BNP also lost all its seats on Barking and Dagenham Council.

A 2007 appointment as Minister of State in the Department of Culture was temporarily interrupted when she took leave to look after her terminally ill husband, and she returned to the post in 2009. A year later, Margaret Hodge was elected by MPs to the Chair of the PAC. According to its website, “The Committee scrutinises the value for money – the economy, efficiency and effectiveness – of public spending and generally holds the government and its civil servants to account for the delivery of public services.“ It has been said that under Hodge’s leadership, the Committee actually held civil servants to account, contrary to established practice. I think many of us can bear witness to this.

Margaret Hodge was sworn into the Privy Council in 2003. She was made a MBE in 1978, and appointed DBE in August 2015. She is yet another of those people I want to be when I grow up.

Scroll down for profiles of Dame Zaha Hadid, Josephine Baker, Dame Stephanie Shirley, Dame Ellen Terry, Baroness Boothroyd, Dame Mary Quant and many more.

Dame Zaha Hadid

Dame Zaha Hadid, whose soaring structures left a mark on skylines and imaginations around the world and in the process reshaped architecture for the modern age, died suddenly last week. She was not just a rock star and a designer of spectacles; she also liberated architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity. Geometry became, in her hands, a vehicle for unprecedented and eye-popping new spaces but also for emotional ambiguity. Her buildings elevated uncertainty to an art, conveyed in the odd ways one entered and moved through those buildings and in the questions her structures raised about how they were supported.

She was born in Baghdad on October 31, 1950. Her father was an industrialist, educated in London, who headed a progressive party advocating for secularism and democracy in Iraq. Baghdad was a cosmopolitan hub of modern ideas, which clearly shaped her upbringing. She attended a Catholic school where students spoke French, and Muslims and Jews were welcome. After that, she studied mathematics at the American University in Beirut (she would later say her years in Lebanon were the happiest of her life). Then, in 1972, she arrived at the Architectural Association in London, a centre for experimental design. She recalled, of her time there, that they “taught me to trust even my strangest intuitions.”

Strikingly, Dame Zaha never allowed herself or her work to be pigeonholed by her background or her gender. Architecture was architecture: it had its own reasoning and trajectory. And she was one of a kind, a path breaker. In 2004, she became the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s Nobel; the first, on her own, to be awarded the RIBA Gold Medal, Britain’s top architectural award, in 2015.

Not one to compromise or concede much to those who called her works impractical, indulgent and imprudent, from early on she made the most, creatively speaking, of what commissions she got. When her Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, a relatively modest project, opened in 2003, Herbert Muschamp, then architecture critic for The New York Times, declared it “the most important American building to be completed since the end of the Cold War.” The Centre can, he said, “be experienced as an exercise in heightening the mind-body connection.” It “presents vantage points of sufficient variety to keep photographers snapping happily for many years to come,” he added.

It took years before she won major commissions in Britain, where she became a citizen and established a thriving office. Her Aquatics Centre in London, built for the 2012 Olympics, was a cathedral for water sports, with an undulating roof and two 50-meter pools. It has become a city landmark and neighbourhood attraction, bustling with children and swimmers.

She embodied, in its profligacy and promise, the era of so-called starchitects, who roamed the planet in pursuit of their own creative genius, offering miracles, occasionally delivering. “She was bigger than life, a force of nature,” as Amale Andraos, the Dean of Columbia University’s architecture school, described her. “She was a pioneer.” She was – for women, for what cities can aspire to build and for the art of architecture.

Josephine Baker 1906 – 1975

While Josephine Baker was not a Dame in the UK honours system, her recognition by the French Government and eventually the USA, has her honoured in such a way that we have included her in our actual Dames.

She was born on June 3, 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri. Her mother, Carrie McDonald, was a washerwoman who had given up her dreams of becoming a music-hall dancer. Her father was a vaudeville drummer and abandoned Carrie and Josephine shortly after her birth. Carrie remarried soon thereafter and had several more children in the coming years.

To help support her growing family, at eight years old Josephine cleaned houses and babysat for wealthy white families, often being poorly treated. She briefly returned to school two years later before running away from home aged thirteen and finding work as a waitress at a club. She took up dancing, honing her skills both in clubs and in street performances. By 1919, at just fourteen, she was touring the United States performing comedic skits. In 1923, she landed a role in the musical Shuffle Along as a member of the chorus, and the comic touch that she brought to the part made her popular with audiences. These early successes led her to move to New York City and she was soon performing along with Ethel Waters, in the floor show of the Plantation Club, where again she quickly became a crowd favourite.

In 1925, at the peak of France’s obsession with American jazz and all things exotic, she travelled to Paris to perform in La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. She made an immediate impression on French audiences when she performed the Danse Sauvage, in which she wore only a feather skirt. The following year, at the Folies Bergère, her career would reach a major turning point. In a performance called La Folie du Jour, she danced wearing little more than a skirt made of 16 bananas. Her comment on the dance was ‘I wasn’t really naked, I simply didn’t have any clothes on.’ The show was wildly popular with Parisian audiences and she was soon among the most popular and highest-paid performers in Europe, gaining the admiration of cultural figures like Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and e. e. cummings and earning herself nicknames like ‘Black Venus’ and ‘Black Pearl’. She also received more than 1,000 marriage proposals.

Capitalizing on this success, Baker sang professionally for the first time in 1930, and several years later landed a couple of film roles as a singer in Zou-Zou and Princesse Tam-Tam. The money she earned from her performances allowed her to purchase an estate in Castelnaud-Fayrac, in the southwest of France. She named the estate Les Milandes, and soon moved her family there from St. Louis.

In 1936, riding the wave of popularity she was enjoying in France, she returned to the United States to perform in the Ziegfield Follies, hoping to establish herself as a performer in her home country as well. However, she was met with a generally hostile, racist reaction and returned to France, crestfallen at her mistreatment. On returning, she married and obtained citizenship from the country that had embraced her as one of its own.

When World War II broke out, she worked for the Red Cross during the occupation of France. As a member of the Free French forces she also entertained troops in both Africa and the Middle East. She also worked for the French Resistance, at times smuggling messages hidden in her sheet music and even in her underwear. For these efforts she was awarded both the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Resistance, two of France’s highest military honours.

Following the war, she spent most of her time at Les Milandes with her family. In 1947, she married French orchestra leader Jo Bouillon, and from 1950 began to adopt babies from around the world. She adopted 12 children in all, creating what she referred to as her ‘rainbow tribe’ and her ‘experiment in brotherhood’. During the 1950s, she frequently returned to the United States to lend her support to the Civil Rights Movement, participating in demonstrations and boycotting segregated clubs and concert venues. In 1963, she participated, alongside Martin Luther King Jr, in the March on Washington, and was among the many notable speakers that day. In honour of her efforts, the NAACP eventually named May 20th ‘Josephine Baker Day’.

After decades of rejection by her countrymen and a lifetime spent dealing with racism, she performed at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1973 and was greeted with a standing ovation. She was so moved by her reception that she wept openly on stage. The show was a huge success and marked her comeback to the stage.

In April 1975, she performed at the Bobino Theatre in Paris, in the first of a series of planned performances celebrating the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut. Numerous celebrities were in attendance, including Sophia Loren and her close friend Princess Grace of Monaco. Just days later, on April 12, 1975, she died in her sleep of a cerebral haemorrhage. She was 69.

On the day of her funeral, more than 20,000 people lined the streets of Paris to witness the procession, and the French government honoured her with a 21-gun salute, making her the first American woman in history to be buried in France with military honours. What a Dame!

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Always partial to a spot of Bach, I pricked up my ears when I heard some being played on a repeated episode of Desert Island Discs the other day, and then became completely transfixed by the story the interviewee, Dame Stephanie Shirley, had to tell.

In 1939, at the age of five, Vera Bluthal arrived in Britain on a Kindertransport. In 1993, on her retirement, she sold the company that she had set up for £6 in 1962 for £150m. Since then she has given away most of this money, saying ‘I need to justify why my life was saved.’

Dame Stephanie’s company was built on positive discrimination. To get round the difficulties of trying to make headway in the nascent IT industry as a woman, she started Freelance Programmers recruiting qualified professional women who had had to leave their employment on marriage or pregnancy. Flexible working, job-sharing, co-ownership: she was a pioneer of all these innovative employment practices.

Her approach paid off, helped by her ruse of changing her name to ‘Steve’ on her business development letters so as to get a foot in the door of potential clients. In time, even big names were using her companies’ products – the programming of the black box flight recorder on Concorde was one of them – never dreaming that the work would have been done by ‘a bunch of women working in their own homes.’

But the domestic life underpinning all this professional and scientific success was in crisis. At the age of three, her only child, Giles (born after several miscarriages), was diagnosed with profound autism. As he grew, his uncontrollable rages and violent attacks put an immense strain on Dame Stephanie’s marriage and her ability to run her company, leading her to contemplate suicide. Eventually she had a complete mental breakdown.

She recovered, but her relationship with her husband, Derek, continued to suffer, and in 1998 they agreed to separate. A few months later Giles, by now 35, died of an epileptic seizure. The grief and desolation that followed drew her and Derek together again. She has said that there hasn’t been a day when she hasn’t missed Giles, despite his traumatic effect on the family.

Not surprisingly, much of her philanthropy has focused on supporting people with autism. She founded a school in Berkshire, Prior’s Court, providing 70 school and 20 college places; and has funded research by the Autism Research Centre. But she has also funded the Oxford Internet Institute, dedicated to the study of the social impact of the web, with a view to shaping policy and research in this area.

Now in her eighties, she has recently appeared on the Women’s Hour list of the 100 most powerful women in Britain, and on the Science Council’s list of the top 100 practising scientists in the UK. And if such innovation and resilience weren’t remarkable enough, the luxury she chose to alleviate her abandonment on Radio 4’s desert island was truly inspirational: Henry Moore’s Mother and Child.

Scroll down for profiles of Dame Ellen Terry, Baroness Boothroyd, and Dame Mary Quant.

Dame Ellen Terry 1847-1928

The more I find out about different dames, the more I like them. Ever since we launched damesnet I’ve been meaning to write an appreciation of Ellen Terry. This is for two reasons: the first, naturally, is because Dame Terry was one of the most popular and successful stage performers of her time. The second is that there is a family connection, albeit tenuous.

Ellen Terry was born into a large theatrical family and became a child actress, encouraged by her parents. She performed in London and took part in provincial tours, but this was cut short at 16 when she married the painter George Frederick Watts, having been his artistic model. The marriage ended 10 months later, and Ellen Terry returned briefly to the stage.

Her most memorable performance at this time, in terms of her future career, was playing Katherina with Sir Henry Irving in The Taming of the Shrew. However, soon afterwards Terry met Edward Godwin, the architect and theatrical designer, and in 1868 she gave up acting to move to Hertfordshire with him. The couple lived together for six years and had two children, but when their relationship broke up Terry moved back to London and once again resumed her theatrical career.

The stage partnership with Irving resumed in 1878, and for 24 years the pair were the glittering couple of the London stage, in particular at the Lyceum Theatre, which Irving developed as a centre of excellence, renowned for its productions of Shakespeare.

During this period Terry played most of the key female roles in Shakespeare’s plays, including Ophelia, Lady Macbeth, Desdemona, Cordelia, Portia, Juliet and Beatrice. She and Irving also toured extensively in the UK and across the US. She was famous for her beauty and her acting skills, and was equally at home in comic and classical roles.

There were two more marriages, but neither of them would appear to have been significant relationships. An actor, Charles Kelly, became her second husband in 1878, but this did not last, and he died in 1885. The final marriage in 1907 was to the American actor James Carew; he was much younger, but again it ended quite quickly, although they remained friends.

Another fascinating side to Terry’s life was her friendship with George Bernard Shaw. They started corresponding in 1892, initially writing about a stage protégé of Terry, and then changing to more personal topics. The exchanges died away for a while, and were then revived by Terry in 1895. By this time Shaw was an established dramatist with an interest in writing plays with strong parts for women. From then on much of their correspondence was about the state of the theatre. Although the two lived near each other, they chose to maintain their relationship through their letters. Shaw described it as “a paper courtship, perhaps the pleasantest and most enduring of all courtships.”

In 1902, Terry’s partnership with Irving came to an end, but her theatrical career continued. It is during this period that my link with her can be claimed. My mother-in-law’s maiden name was Blascheck, and her grandfather was Joseph Blascheck, always known as J.B. He was born in London and when his father died his mother emigrated to Melbourne with her children. J.B. started a career as an elocutionist and humourist, before moving back to London around 1898 with his wife Beatrice and two children, probably to develop his career in the theatre.

Their third son Ballard was born in 1904: Ellen Terry’s maiden name was Ballard, and it is possible that this name was in honour of the friendship with Terry. Then in 1914, just before the outbreak of the First World War, J.B. and Ellen Terry did a three-month tour of Australia and New Zealand, with J.B. as her actor manager.

They arrived in Melbourne on May 4 1914, and John Singer Sergeant’s study in monochrome of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth was presented to the Melbourne National Gallery. Of this particular costume Terry had written to her daughter that “it is in colour that it is so splendid. The dark red hair is fine. The whole thing is Rossetti—rich stained-glass effects.”

The tour took in performances in Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney, Wellington and Auckland before returning to England in August 2014.

In 1925 Ellen Terry was made a Dame Grand Cross of the British Empire, dying three years later at her cottage in Hythe, Kent. One further postscript on the family connection: J.B.’s son Ballard became an actor in his own right, changing his surname to Berkeley. His most famous role was the Major in Fawlty Towers. I like to think Ellen Terry would have approved.

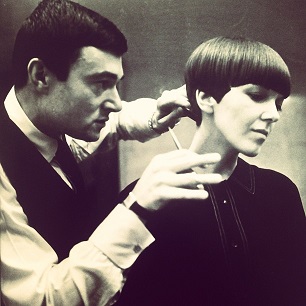

Better late than never: Dame Mary Quant

It came as something of a surprise to me that Mary Quant was only created a Dame Commander of the British Empire earlier this year, though considering dame designate Petula Clark still hasn’t been made a dame, I don’t know why I was surprised.

Mary Quant’s daisy logo became a ubiquitous symbol long before we all knowingly bought into the power of branding, standing for all that was fresh, informal and freewheeling even as it helped to build a fashion, home and cosmetics empire.

Although she is most closely associated with the miniskirt, she modestly assigned the credit for it elsewhere (though she coined the term): ‘It was the girls on the King’s Road who invented the mini . . . I wore them [skirts] very short and customers would say “shorter, shorter”.’ So it was a classic example of being in the right place at the right time. She was designing clothes that allowed young women to move freely (with no hats or gloves needed) at the precise moment that they were wanting to dress differently from their mothers, and, what’s more, could afford to do so as Britain emerged from post-war austerity.

But it was about more than just the clothes. Her trademark Vidal Sassoon bob launched a sharp, clean androgynous look (sadly not something that those of us whose hair tended more naturally to the Marcel wave could aspire to), and the brightly coloured tights that complemented her outfits rendered flesh-coloured legwear obsolete for a generation of women.

In commercial terms, though, it was her cosmetics range that proved the most enduring: blue nail varnish, silver eyeliner – and a refreshing honesty about what cosmetics could achieve. The advertising for her Skin Drink moisturiser stressed that moisturise was all it would do: no added radiance, firmness, etc., etc., were promised. The cultural significance of this range of cosmetics is demonstrated by the fact that many examples of it are to be found in the archive of the Museum of London.

Not being a fashionista who haunts the King’s Road, I was also surprised to find that a Mary Quant shop has reopened there, on the site of her original Bazaar boutique, which was launched 60 years ago (who knew – or remembers – that she had been going since 1955?). The clothes and cosmetics are still available, but the fact that you can open the Mary Quant website in Japanese gives a clue to the current ownership of the brand. We may only have one such shop in the UK, but there are around 200 Mary Quant colour shops in Japan.

She may have bowed out of the brand she launched, but Mary Quant remains an influential figure, and of course, we are grateful to her for a suitably damely quote: ‘Good taste is death, vulgarity is life!’

Happy Birthday, Dame Vivienne Westwood

It seemed totally implausible that we could ignore the birthday on April 8th of one of the most original and flamboyant examples of damehood currently around. She is of course Dame Vivienne Westwood.

Ms Westwood is one of those dames who are always ahead of the curve; her partnership with Malcolm McLaren in the 1970s resulted in their showcase shop in London’s Kings Road, variously called ‘Let it Rock’/‘Sex’/’Too fast to live too young to die’ and ‘Seditionaries’. Nowadays it is called more prosaically ‘World’s End’, reflecting the local name of that part of the Kings Road.

Westwood made the clothes that McLaren designed, and a new line in fashion was born that became the defining brand image for punk rock: bondage gear to include safety pins, razor blades, bicycle chains and dog collars, much of which against a backdrop of tartan, and crowned with gelled multi-coloured spiky hairdos and . All these accessories were used to complement Westwood’s particular style of cutting garments that turned mainstream fashion on its head. When McLaren became manager of the Sex Pistols, the band performed kitted out in Westwood from head to toe, and punk fashion was born. Westwood has been quoted as saying ‘He cared passionately for clothes and transformed me from a Dolly Bird into a chic, confident dresser.’

Once lesser known fact about Dame V is that for many years she was a primary school teacher. After one term of studying fashion and jewellery at Harrow School of Art she was convinced that she would never be able to earn a living in the art world, so she trained as a teacher and taught for over 10 years until Let it Rock opened in 1971.

Fashion aside, Westwood has supported a series of left of centre causes, including the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, civil rights group Liberty, and environmental issues including climate change and water usage. Politically, she backed Labour for many years until switching allegiance to the Conservatives in 2007. In early 2015 she declared her support of the Green Party, and is reputed to be backing them financially in advance of the forthcoming General Election.

Her designs have always reflected her political and ethical stance – ‘I reach people — people who read fashion magazines for instance – who would never have heard about some of this otherwise. My main point, though, is quality rather than quantity. What I’m always trying to say is: buy less, choose well, make it last; thought sometimes I might as well say, “Buy Vivienne Westwood”!’ There are few A- list members across the spectrum from royalty to media stars to top models that have not been seen in Westwood at some point in their career or another.

Westwood has continued to evolve in a way that ensures her designs are always in demand. ‘My clothes have an identity,’ she says, ‘They have a character and a purpose. That’s why they become classics. Because they keep on telling a story. They are still telling it.’

In 1992 Vivienne was awarded the OBE, and in 2006 she was made a DBE for ‘services to British fashion’. Happy birthday Dame V!

Dame Julian of Norwich

I have just had the surreal experience of going onto a website to read about Dame Julian of Norwich, the celebrated 14th century mystic, and finding under her name a crude sketch of a banana with the legend ‘Cut down a bit of belly fat every day by never eating these five foods.’

I think it’s safe to say that Dame Julian had her mind on higher things, and even if she did take time off from her meditations, it’s likely that she was more worried about the plague than her waistline.

Julian (not her real name, which is unknown) was probably born in 1342. At the age of 30 she became gravely ill and experienced a series of visions of Jesus while she was on what was assumed would be her deathbed. She recovered, and the visions disappeared, but she wrote of them vividly and explored their meanings. These writings were published in 1395 as Revelations of Divine Love, a narrative of around 11,000 words that is believed to be the earliest surviving book written by a woman. Some thirty years later she expanded these writings with a commentary that ran to 63,500 words.

As to damehood, it was the mystic Margery Kempe (herself the author of the first autobiography written in English) who referred to her as Dame, a title that was interchangeable with ‘Lady’ at the time.

Dame Julian’s theology emphasized God’s compassion. She saw God as both mother and father, and specifically characterised Jesus as a wise, loving and merciful mother, likening the relationship between mother and child as the closest earthly relationship to the divine one between an individual and Jesus. Though these views were controversial, they were not challenged by the church authorities. Who can say whether this was because of her status as a respected anchoress (a woman who has withdrawn from the world), or because the views of a woman counted for little? Nevertheless, her writings were edited by well-established (male) clerics, and went on to gain wide circulation.

She remains an influential spiritual thinker, whose belief that sin arose from ignorance rather than evil sits more easily with current thinking than it did with the prevailing theology of her own time. This held that people were wicked and therefore subject to the harsh punishments of a judgmental God — perhaps only to be expected in the context of the Black Death and peasant revolts. The most famous extract from her writings reflects her profound belief in divine compassion: ‘All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.’ T.S. Eliot used this in The Four Quartets, and it continues to have resonance, despite current evidence to the contrary as great as any that the Middle Ages were able to inflict.

Dame Julian’s cell at St Julian’s Church in Norwich can still be visited today, and there is an annual Julian Week, incorporating a Julian Festival on the second Saturday in May to celebrate her Commemoration Day.